Edward King Cox (1829-1883), grazier, and James Charles Cox (1834-1912), medical practitioner, were the eldest and third sons of Edward Cox, M.L.C., of Fernhill, Mulgoa, and his wife Jane Maria, daughter of Richard Brooks, and grandsons of William Cox. Both were born at Mulgoa, Edward on 28 June 1829 and James on 21 July 1834. Until James was about 13 the boys lived at Mulgoa and attended the parish school of Rev. Thomas Makinson; in 1847 they went to The King’s School at Parramatta for about three years.

After leaving school Edward lived on his father’s sheep stations at Rawdon, Rylstone, in the Mudgee district, and his leases on the Namoi. In 1852 he accompanied his brother to Europe where he studied sheepbreeding and inspected the principal flocks in England and on the Continent. At Tralee, County Kerry, on 19 May 1855 he married Millicent Ann, daughter of Richard J. L. Standish. Soon afterwards he returned to take charge of his father’s stations.

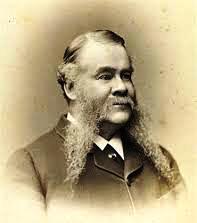

Edward King COX

Edward was an outstanding breeder of stud stock. He inherited his father’s merino stud at Rawdon, Rylstone, and by careful breeding won world renown as ‘the great improver of the Australian Merino’. He won awards in many countries for his wool, particularly the grand prize at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. Edward brought together at Fernhill, Mulgoa, his stud Shorthorn cattle and thoroughbred horses in 1868. His chief sires, Yattendon and Darebin, both won the Sydney Cup; he also imported stud mares from England and bred the Melbourne Cup winners, Chester and Grand Flaneur. In 1873, with John Agar Scarr, Edward was joint editor of The Stud Book of New South Wales.

In July 1874 Henry Parkes appointed Cox to the Legislative Council in the squatting interest, although he was ‘as yet an untried man in public life’. Because of arthritis and a trip to England he was never active in politics. He died on 25 July 1883 at Mulgoa, survived by his widow, who died on 11 March 1902 aged 70, five sons who followed his pastoral interests, and a daughter Mary, who in September 1881 married John Archibald Anderson, a grazier, of Newstead, Inverell. Cox’s estate was valued at £95,572. His home, Fernhill, still stands, a fine example of Georgian architecture, built by his father in 1840 of local sandstone.

As a child in the bush around Mulgoa James had played with Aboriginal children from whom he learnt the lore of native birds and animals. He showed such interest in natural history that his father determined to make him a doctor and apprenticed him for three years to Henry Grattan Douglass at a fee of 300 guineas. At the Sydney Infirmary he learnt dispensing, acted as a clinical clerk, assisted at post mortems and in 1852 witnessed an early operation performed under chloroform. In his last year of apprenticeship he became assistant to Professor John Smith, who had just begun chemistry lectures at the University of Sydney in what became the Sydney Grammar School. Cox also made himself useful in setting up the museum next door. He then continued his studies at Edinburgh (M.D., 1857; F.R.C.S., 1858) and returned to New South Wales where he registered as a medical practitioner on 1 February 1859.

Through his social, government and vice-regal connexions Cox enjoyed a very extensive private practice. He became recognized as a leading physician in Sydney and was for many years medical adviser to the Australian Mutual Provident Society. In 1875 he joined other prominent doctors in defending their profession against his former tutor, Professor Smith, who as dean of the Sydney medical faculty had allegedly reflected on the skill, qualifications and sobriety of colonial medical practitioners.

Cox’s contributions to medical education began at the Sydney Infirmary where he was honorary physician in 1862-72, honorary surgeon in 1877-79 and honorary consulting physician in 1873-76 and 1880-1911. His attempts to effect some reform in the technical management of the hospital were at first frustrated, and the pharmacopoeia he compiled in 1870, based largely on London editions, was not accepted till the late 1870s. But his services to Sydney Hospital were remembered in the dedication of Frederick Watson’s The History of the Sydney Hospital from 1811 to 1911 (Sydney, 1911), as one ‘who, for sixty-one years, has watched and assisted [in its development] as student, hon. physician, hon. surgeon, hon. consulting physician and director’. In 1883-1901 Cox lectured at the University of Sydney on medical principles and practice and was an honorary physician at Prince Alfred Hospital in 1889-1901. A student later recalled ‘the noble old face, with its gentle and courtly expression, the well-known stoop, the slightly bowed legs, the soft elastic-sided boots of French kid, and the dentures that never quite fitted … His great kindness of heart, his hatred of anything mean, and his extreme care in avoiding any possible hurt to anyone’s feelings, endeared him to everyone’. He was particularly remembered by final year students for his annual picnics at Newport or the Spit.

Cox retained his early love of natural history all his life. On his return from Britain in 1859 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of New South Wales (then the Philosophical Society). He was first president in 1862 and long a member of the New South Wales Board of Fisheries, and a trustee of the Sydney Museum, to which he left his collection of Australian land shells. He was first secretary of the Entomological Society formed in 1862 and, after it became the Linnean Society of New South Wales in 1874, was its president in 1881-82; in 1868 he had been elected a fellow of the Linnean Society of London. His contributions to the journals of these societies were mainly on the conchology of Australia and the South Sea islands, but he also wrote on such subjects as the government regulation of oyster beds, and Aboriginal drawings, wax figures and stone implements. Among his works of reference published in Sydney were Catalogue of the Specimens of the Australian Land Shells (1864), A Monograph of Australian Land Shells (1868), An Alphabetical List of the Fishes Protected Under the Fisheries Act of 1902 (1905), and an Alphabetical List of Australian Land Shells (1909).

As a member of an old colonial family Cox took an antiquarian’s interest in Australian history. He was first president of the Australasian Pioneers’ Club, a member of the Australian Club for over fifty years, and a founder of the Historical Society in 1901. Although an obituarist in the Sydney Morning Herald considered him ‘very reticent in regard to himself’ and reluctant to write his autobiography, he was always good company at the leading Sydney clubs where his after-dinner speeches recalled early colonial days and the exploits of his family.

In Scotland on 29 September 1858 Cox married Margaret Wharton, daughter of John Maclellan, a merchant of Greenock, and his wife Jane, née Wharton. Of their four sons, James Wharton (1859-1911) and Allaster Edward (1864-1908) graduated in medicine at Edinburgh; Arthur Brooks (1866-1924) studied in London (M.R.C.S., 1890) and practised in Sydney as a dentist; the eldest of their six daughters, Millicent, married in 1890 Montague Peregrine Albemarle Bertie (twelfth Earl of Lindsey), who had been aide-de-camp to the governor, Lord Carrington, in 1885-88. Cox’s wife died on 21 February 1876 aged 36, and on 18 March 1878 he married Mary Frances, daughter of Dr William Benson, a medical practitioner in Hobart, and his wife Louisa Frances, née Lakeland; she died childless at 52 on 1 October 1902. Soon afterwards Cox married a widow, Emma, whose first husband was a grandson of John George Gibbes; they had one daughter. Cox died at his home in Mosman, Sydney, on 29 September 1912 and was buried in the family grave at Mulgoa.

Two portraits of J. C. Cox, one by Herbert Beecroft, are in the Australasian Pioneers’ Club.

Source: Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cox-edward-king-3278, accessed 14 April 2016.